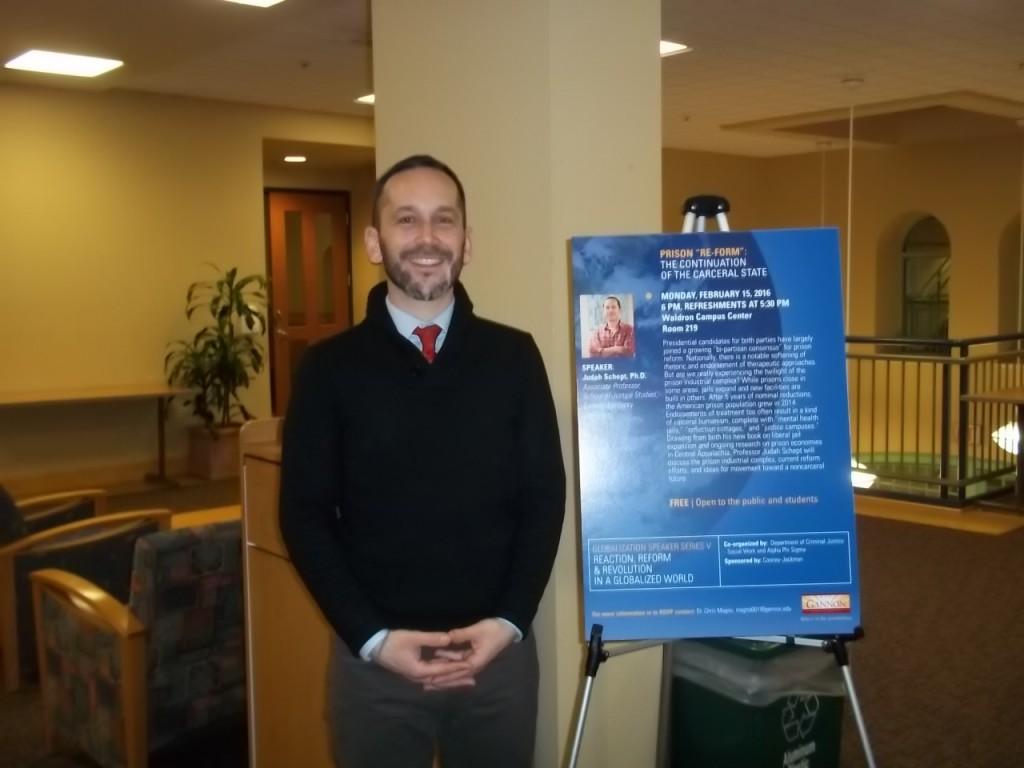

Gannon University students and faculty learned about the importance of America’s incarceral state during a lecture in the Globalization Series sponsored by Alpha Phi Sigma Monday.

Judah Schept, Ph.D, a professor at Eastern Kentucky University, lectured on prison reform in the sense of re-doing prisons and not just improving the system.

“Broadly speaking, I study mass incarceration,” Schept said. Although he initially studied criminal justice, Schept said his work tends to draw more from social theories and social anthropology.

Mass incarceration covers more than those imprisoned, Schept said. The carceral state characterizes American society because it can shift its contours and has been a result of and directly produced anti-black racism.

These attitudes developed in the Reconstruction era following the Civil War, and were reinforced using Jim Crow laws. The carceral state has been referred to recently by presidential candidates as the New Jim Crow, in that it perpetuates racism.

Schept said the carceral state is also relevant today in a world where unprecedented attention is given to prisons, police and their transformation. More than half the states in the U.S. have passed some kind of sentencing reform, and there is talk of “banning the box” that asks if potential employees have ever been arrested.

“Much of what I think needs to be done is to engage directly some of these contradictions in what we’re doing at the moment,” Schept said. “What really, in fact, makes us safe?”

America houses 6 percent of the world’s population, but 25 percent of the world’s prisoners.

In Bloomington, Ky., proposals were made for a “Justice Campus” that would serve as what Schept called a social hub of carceral humanism.

The campus was part of a plan to develop 85 unused acres of land that formerly belonged to RCA into a lock-down with the feel of a college campus and possible food initiatives if the land was farmed by inmates. The proposal was backed by liberal and progressive thinkers in the community, Schept said.

The Justice Campus was more than a spatial fix for unwanted land, however. Schept said one of the supporters said the campus would be good to “take care of all the poor people” in one place. Besides the prison complex, the campus would house Bloomington’s welfare center and proposed other services, like a laundromat.

Schept said the terms used in support of such a building mimic a critque of incarceration but in fact support it. Another example of the current carceral state Schept discussed are the prisons built on top of former coal mines in central Appalachia.

“Once coal is gone and the land devalued, the prison comes in as a sort of socioeconomic fix,” Schept said.

Schept said that identifying prison complexes as economically good helps to keep the carceral state alive.

“How do we challenge prison building when it’s seen as the only possible economic solution for that region?” Schept said. “It’s hard to think about a replacement economy that would take the place of coal or a prison.”

Schept stressed the importance of thinking regionally when it comes to such economic issues and making a just transition for local economies.

Matt Moreland, a senior criminal justice major, said he attended Schept’s lecture because he was intrigued by Schept’s research when he presented to one of Moreland’s classes.

“It was a little hard to follow, but hearing him speak earlier made it easier to follow,” Moreland said.

Moreland said some of the topics were things he’d considered before, like prisons being called the new Jim Crow.

“It could be legitimate considering the impending amount of African-Americans in prison and impoverished,” Moreland said.

KELSEY GHERING

[email protected]