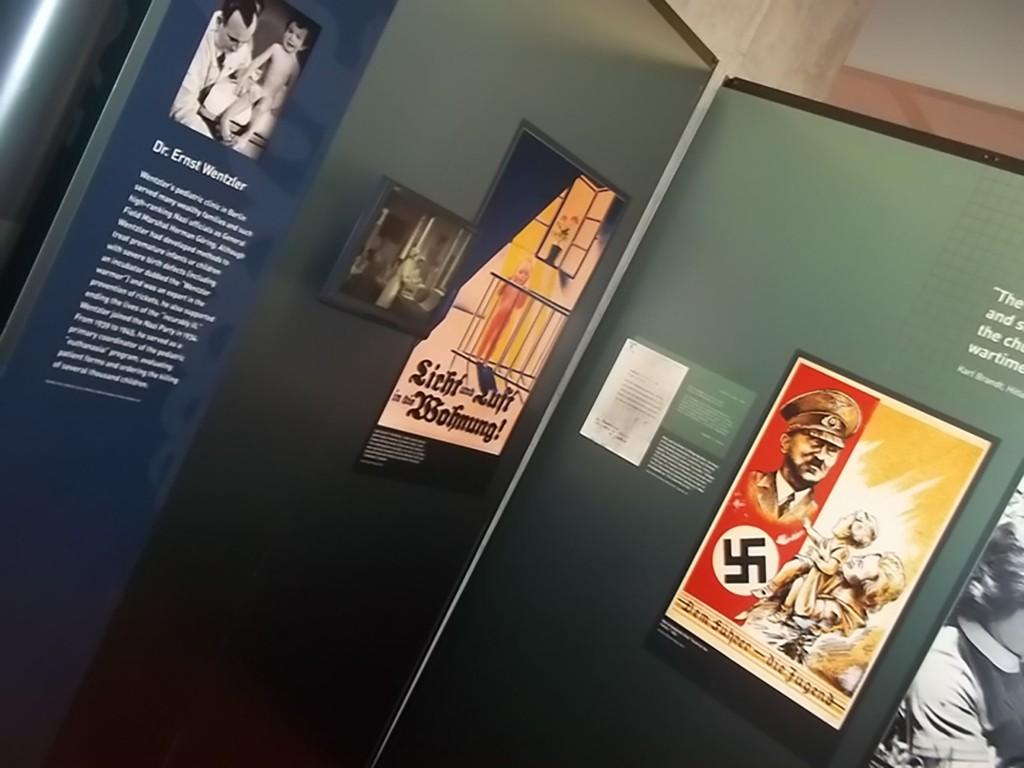

A grand opening lecture for the Deadly Medicine traveling exhibit at Nash Library Thursday built the framework for conversations about why the Holocaust happened.

Jeff Bloodworth, Ph.D., chair of Gannon University’s history department and an associate professor of history, was the featured speaker. The Rev. Michael Kesicki offered an invocation prayer and Rabbi Emily Losben said the Benediction, including a poem in Hebrew.

Bloodworth said the exhibit did a good job of showing how eugenics became a pseudoscience in Germany, but we still ask how it could have happened.

“The Holocaust is so much worse than what you imagine,” Bloodworth said. Seventy-five percent of 6 million Jews were killed in 20 months.

“We know nothing about the sites where killings occurred,” Bloodworth said. Auschwitz is well- known for its survivor accounts, but the deadliest sites were elsewhere at low budget camps like Rinehart, Bloodworth said.

Bloodworth said these were not supernatural events that occurred outside history, but things that happened for explicable reasons. He went on to explain the nature of Jews as societal targets.

The Catholic Church believed Jews should suffer on earth for rejecting Christ, and it became doctrine to segregate Jewish people in Catholic communities. This practice became grounds for European anti-Judaism.

Anti-Semitism began with the belief that Jews possess certain inherent, destructive traits. Industrialization in the 19th century de-skilled millions. This resulted in millions migrating in search of jobs.

The traditionally segregated Jewish population was released from the ghetto and prospered in the workforce. Thirty-two percent of millionaires were Jewish.

Wilhem Mar, a failed German businessman, coined the term “anti-Semitism” to show that anti-Judaism was about politics and scientific fact. This was a popular time for people to explain society using Darwin’s theory of evolution.

By using Darwin for credibility, the Nazis were able to invent pseudoscience practices like studying nose sizes and language roots of Jews.

Though the anti-Semitists were not successful in elections until after World War I, Bloodworth said the anti-Semitist campaign took on a redemptive quality, and the Nazis saw these attitudes as a reasonable response to a new threat. The people followed.

“Humans want security; they tend to follow the ideas of those in charge,” Bloodworth said.

Bloodworth said after the Holocaust, world economies were more careful, foreign policy was reinstated with the establishment of the United Nations and the result is that we live in an age of remarkable stability and security.

“In comparison to human history, we live in boring times,” Bloodworth said. “The response to the Holocaust should be viewed as relatively heartening.”

Losben said during Benediction that we have to remember the Holocaust and never let it happen again.

“It is our responsibility and our job to remember, whether you’re Jewish or not,” Losben said.

Brandon Saranti, a freshman occupational therapy and Spanish dual major, said he attended the lecture because he takes history with Bloodworth and recently discovered he had a German relative who died in the Holocaust.

“It was pretty powerful,” Saranti said. “My favorite part was the Rabbi.”

KELSEY GHERING

[email protected]